The Snow-Table

1996

motorized sculpture

women’s blouses, skates, skis, wood, steel, vitrified acrylic, motors, motion sensor with electronic time switch, incandescent lighting

table: 120 x 240 x 160 cm, plus suspended skis in motion

documentation: – photo©Diane Landry – video camera©Boris Firquet – video editing©Diane Landry

2013

- The Cadence of All Things, Cameron Art Museum, Wilmington (North Carolina, USA).

2012

- Correspondances, curator: Nicole Gingras, Manif d’art 6 – Machines : Les formes du mouvement, Musée de l’Amérique française, Quebec City (Quebec, Canada).

2008

- Les défibrillateurs, curator: Eve-Lyne Beaudry, Musée d’art de Joliette, Joliette (Quebec, Canada).

1999

- Humeur à patiner and L’Étreinte atroce, Musée d’art contemporain des Laurentides, Saint-Jérôme (Quebec, Canada).

- Humeur à patiner and L’Étreinte atroce, Centre d’exposition d’Amos, Amos (Quebec, Canada).

- Humeur à patiner, Artcite Inc., Windsor (Ontario, Canada).

1998

- Humeur à patiner, Artemesia Gallery, Chicago (Illinois, USA).

- Humeur à patiner and L’Étreinte atroce, curator: Françoise Balboni, Centre d’Art Contemporain Passages, Troyes (France).

- Structures du quotidien, curator: Carl Johnson, Musée régional de Rimouski, Rimouski (Quebec, Canada).

1996

- Humeur à patiner, Obscure, Quebec City (Quebec, Canada).

- Humeur à patiner, Espace Virtuel, Chicoutimi (Quebec, Canada).

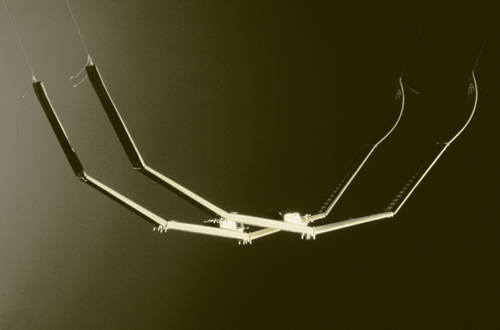

It was not until the creation of The Snow-Table [cat.5] in 1996 that Landry freed herself once and for all from the system of rules that had hitherto structured the collecting of objects she intended to use as raw material. She describes this transition as follows: “The idea of collection was always there, but this time I was looking for something precise and I was the one doing the choosing. It was the first time I formed a collection in that way.6 To make The Snow-Table, she elected to work with women’s blouses, cutting them up and keeping only the collars and sleeves. These were then soaked in acrylic and industrially heated under pressure so that the fabrics hardened and turned glassy and transparent. Landry then put together the pieces to make a table with feet shod in women’s ice skates; on top of this she put a kettle transformed into a skater’s helmet. Cross-country skis hanging above the table tramp in the air, powered by a rotating mechanism made of casseroles. Blouses, skates, skis, casseroles, table and kettle were deliberately chosen to evoke a social reality that the artist wanted to portray in sculpture. The work was actually inspired by the prostitutes she saw every day and who made a deep impression on her when she saw them working the streets during her first winter in the Saint- Roch neighbourhood of Quebec City. The tramping cross-country skis hanging over the snow-table and the ice skates so precariously supporting it conjure up the tough working conditions that street walkers have to face in wintertime.

The objects composing The Snow-Table are used for their metaphorical potential and have a different function from that of artefacts in earlier works. This marks a significant shift in Landry’s practice. From now on a motley assortment of common objects—umbrellas, turntables, skis, ice skates, toys, kettles, water bottles, salad spinners, laundry baskets, mattresses and so forth—would be systematically deflected from their original function to become part of Landry’s own poetic world. This development in her practice becomes evident also in the titles she gives her creations; these too start to convey the multiple meanings suggested by the familiar objects she uses in her installations and performances. While the earlier works had more or less descriptive titles (About 8,000 Kilometres, Utica Project, Parallel Strategies, etc.) in line with the programmed strategies of collecting the objects, now the titles are like mysterious legends or clues left here and there to provide possibilities of interpretation.7

(Extract from the catalog Les Défibrillateurs / The Defibrillators, Musée d’art de Joliette and The Robert McLaughlin Gallery, text: Eve-Lyne Beaudry, p. 78-79-80.)